This GSEB Class 10 Maths Notes Chapter 8 Introduction to Trigonometry covers all the important topics and concepts as mentioned in the chapter.

Introduction to Trigonometry Class 10 GSEB Notes

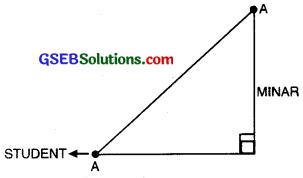

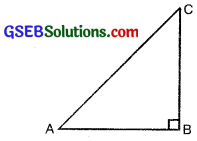

1. If a student is looking at the top of the Minar, a right angled can be imagined to be made, as shown below.

2. Suppose a girl is sitting on the balcony of her house located on the bank of a river. She is looking down at a flower pot placed on a stair of a temple situated nearby on the other bank of a river. A right triangle is made in this situation as shown below.

In all the situations given above, the distances or heights can be found by using some mathematical techniques, which come under a branch of mathematics called ‘trigonometry’. The word ‘trigonometry’ is derived from the Greek words ‘tri’ (meaning three) ‘gon’ (meaning sides), and ‘metron’ (meaning measure). In fact, trigonometry is the study of relationships between the sides and angles of a triangle.

In this Chapter, we will study some ratios of the sides of a right triangle with respect to its acute angles called trigonometric ratios of the angle. We will also define the trigonometric ratios for angles of measure 0° and 90°. We will calculate trigonometric ratios for some specific angles and establish some identities involving these ratios called trigonometric identities.

Trigonometric Ratios

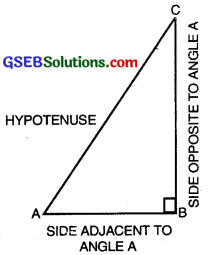

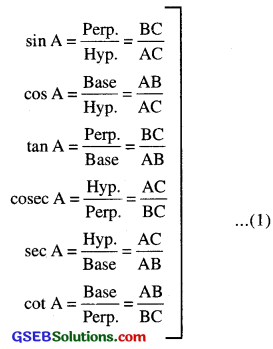

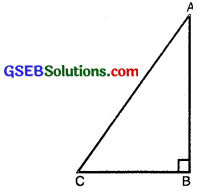

Let us take a right triangle ABC as shown in the fig.

Here, ∠CAB (or, in brief, angle A) is an acute angle. Note the position of the side BC with respect to angle A. It faces ∠A. We call it the side opposite to angle A. AC is the hypotenuse of the right triangle and the side AB is adjacent to ∠A. So, we call it the side adjacent to angle A.

Note that the position of sides change when you consider angle C in place of A (see fig.)

Aryabhatta A.D. 476-550

retained as it is. The word jiva was translated into sinus, which means curve, when the Arabic version was translated into Latin. Soon the word sinus also used as sine, became common in mathematical texts throughout Europe. An English Professor of astronomy Edmund Gunter (1581 – 1626), first used the abbreviated notation ‘sin’.

The origin of the terms ‘cosine’ and ‘tangent’ is much later. The cosine function arose from the need to compute the sine of the complementary angle. Aryabhatta called it kotijya. The name cosinus originated with Edmund Gunter. In 1674, the English Mathematician Sir. Jonas Moore first used the abbreviated notation ‘cos’.

Remark: Symbol sin A is used as an abbreviation for ‘sine of angle A’. It is not the product of ‘sin and A’.

Similar interpretations follow for other trigonometric ratios also.

- sine A is abbreviated as sin A

- cosine A is abbreviated as cos A

- tangent A is abbreviated as tan A

- cotangent A is abbreviated as cot A

- secant A is abbreviated as sec A

- cosecant A is abbreviated as cosec A.

![]()

Trigonometric Ratios of a given Acute Angie :

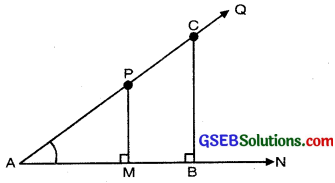

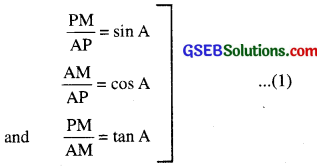

Let ∠QAN be any acute angle, where AQ and AN are two arms of an angle.

Draw PM perpendicular to AN and CB perpendicular to AN.

In right angled triangle APN,

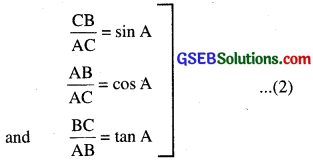

Similarly, in right angled ∆ABC, CB

In ∆APM and ∆ACB,

∠AMP = ∠ABC

∠CAB = ∠CAB

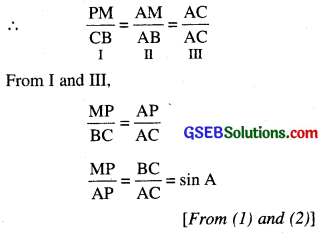

∴ ∆APM ~ ∆ACB [By AA similarity]

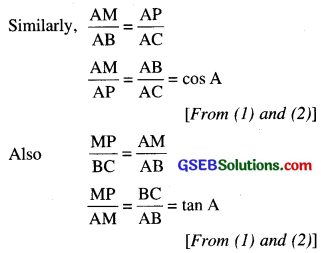

[From (1) and (2)]

This shows that the trigonometric ratios of angle A in ∆PAM not differ from those of angle A in ∆CAB.

So, we conclude that the values of the trigonometric ratios of an angle do not vary with the lengths of the sides of the triangle if angle remains saine.

Trigonometric Ratios of Some Specific Angles

In this topic, we will find Trigonometric Ratio of Angles : 0°, 30°. 45°, 60° and 90°.

Trigonometric Ratios of 0° and 90°

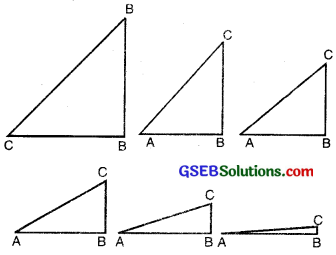

Let us see what happens to the trigonometric ratios of angle A, if it is made smaller and smaller in the right triangle ABC (see fig.), till it becomes zero.

As ∠A gets smaller and smaller, the length of the side BC decreases. The point C gets closer to point B, and finally when ∠A becomes very close to 0°, AC becomes almost the same as AB (see fig.)

When ∠A is very close to 0, BC gets very close to 0 and so the value of sin A = \(\frac{B C}{A C}\) is very close to 0. Also, when ∠A is very close to 0, AC is nearly the same as AB and so the value of cos A = \(\frac{A B}{A C}\)

This helps us to see how we can define the values of sin A and cos A when A = 0°. We define :

sin 0° = 0 and cos 0° = 1.

Using these, we have :

tan0° = \(\frac{\sin 0^{\circ}}{\cos 0^{\circ}}\) = 0

cot0° = \(\frac{1}{\tan 0^{\circ}}\)

which is not defined (Why) ?

sec 0° = \(\frac{1}{\cos \theta^{\circ}}\) = 1 and cosec 0° = \(\frac{1}{\sin 0^{\circ}}\)

which is again not defined. (Why) ?

Remark:

cosec 0° = \(\frac{1}{\sin 0^{\circ}}=\frac{1}{0}\) = not defined

cot 0° = \(\frac{1}{\tan 0^{\circ}}=\frac{1}{0}\) = not defined.

Now, let us see what happens to the trigonometric ratios of ∠A when it is made larger and larger in ∆ABC till it happens 90°. As ∠A gets larger and larger, ∠C gets smaller and smaller. Therefore, as in the case above, the length of the side AB goes on decreasing. The point A gets closer to point B. Finally when ∠A is very close to 90°, ∠C becomes very close to 0° and the side AC almost coincides with side BC (see fig).

When ∠C is very close to 0°, ∠A is very close to 90°, side AC is nearly the same as side BC, and so sin A is very close to 1. Also when ∠A is very close to 90°, ∠C is very close to 0°, and the side AB is nearly zero, so cos A is very close to 0.

So, we define : sin 90° = 1 and cos 90° = 0.

Remark :

- tan 90 = \(\frac{\sin 90^{\circ}}{\cos 90^{\circ}}=\frac{1}{0}\) = not defined

- sec 90° = \(\frac{1}{\cos 90^{\circ}}=\frac{1}{0}\) = not defined .

Trigonometric Ratios of 30° and 60°

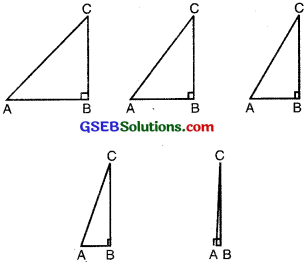

Let us now calculate the trigonometric ratios of 30° and 60°. Consider an equilateral triangle ABC. Since each angle in an equilateral triangle is 60°, therefore,

∠A = ∠B = ∠C = 60°

Draw a perpendicular AD from A to the side BC (see fig.)

Now ∆ABD = ∆ ACD

Therefore, BD = DC

and ∠BAD = ∠CAD (CPCT)

Now observe that:

∆ABD is a right triangle, right angled at D with ∠BAD = 30° and ∠ABD = 60° (see fig.).

As you know, for finding the trigonometric ratios, we need to know the length of the sides of the triangle. So let us suppose that AB = 2a.

Then BD = \(\frac{1}{2}\)BC = a

and AD2 = AB2 – (BD)2

= (2a)2 – (a)2 = 3a2,

Therefore, AD = a\(\sqrt{3}\)

Now, we have:

Similarly,

- sin 60° = \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{AB}}=\frac{a \sqrt{3}}{2 a}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\)

- cos 60° = \(\frac{1}{2}\)

- tan 60° = \(\sqrt{2}\)

- cosec 60° = \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}\)

- sec 60° = 2

- cot 60° = \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\)

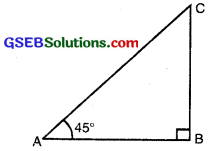

Trigonometric Ratios of 45°:

In ∆ABC, right-angled at B, if one angle is 45°, then the other angle is 45°,

i.e., ∠A = ∠C = 45° (see fig.)

So, BC=AB

[Equal angles have equal sides opposite to it]

Now suppose BC = AB = a

Then by Pythagoras Theorem,

AC2 = AB2 + BC2

= a2 + a2 = 2,

and therefore, AC = a\(\sqrt{2}\)

To find T-ratios of ∠A = 45°

Here Hyp. AC = a\(\sqrt{2}\)

Base (AB) = a

Perpendicular (BC) = a

Using the definitions of the trigonometric ratios, we have:

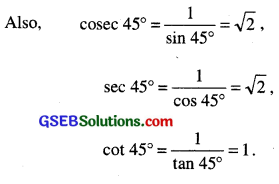

Table for Recalling different values of T-ratios.

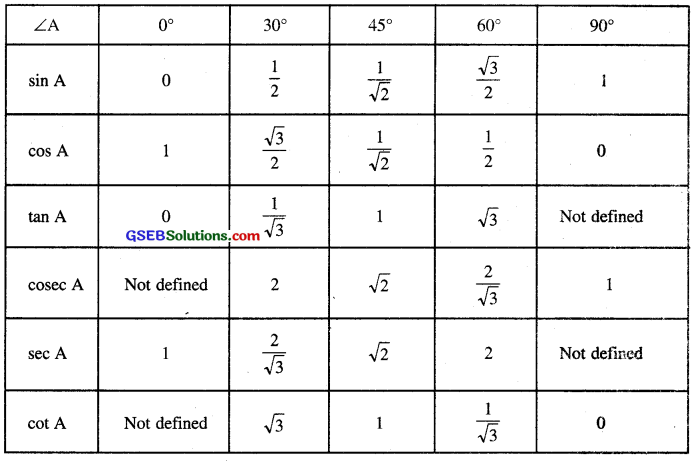

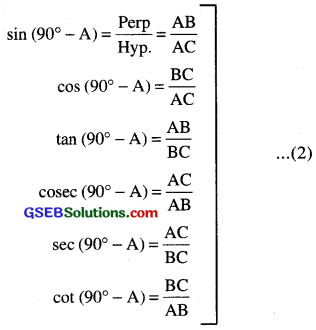

Trigonometric Ratios of Complementary Angles

We know that two angles are said to be complementary if sum of two angles is equal to 90°. Consider a right angled at B.

Since ∠A + ∠C = 90°.

To find T-ratios of angle A.

Hyp. = AC

Base = AB

Perpendicular = BC

Now we will find out the T-ratios of angle

90° – A = ∠C

For ∠C = 90° – A

Hyp. = AC

Base = BC

Perp. = AB

Compare the ratios in (1) and (2) AB

- sin (90° – A) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AC}}\) = cos A

- cos (90° – A) = \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{AC}}\) = sin A

- tan (90° – A) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BC}}\) = cot A

- cot (90° – A) = \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{AB}}\) = tan A

- cosec (90° – A) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AB}}\) = sec A

- sec (90° – A) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{BC}}\) = cosec A

Remarks: When we will change the angle then sin θ, cos θ, tan θ. cot θ, sec θ, cosec θ will also change. To remember the changes add ‘co’ if it is not added, remove ‘co’ if it is added.

![]()

Trigonometric Identities

An equation is called an identity when it is true for the values of the variables involved.

Similarly, an equation involving trigonometric ratios of an angle is called a trigonometric identity, if it is true to all values of the angle(s) involved.

In this section, we will prove the trigonometric identity, and use it further to prove other useful trigonometric identities.

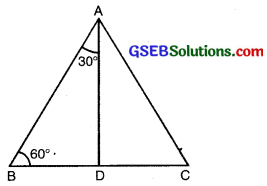

In ∆ABC, right angled at B (see fig.), we have :

AB2 + BC2 = AC2 …(1)

Dividing each term (1) by AC2, we get:

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}^{2}}{\mathrm{AC}^{2}}+\frac{\mathrm{BC}^{2}}{\mathrm{AC}^{2}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}^{2}}{\mathrm{AC}^{2}}\)

i.e., \(\left(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AC}}\right)^{2}+\left(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{AC}}\right)^{2}=\left(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AC}}\right)^{2}\)

i.e., (cos A)2 + (sin A)2 = 1

i.e., cos2 A + sin2 A = 1. …………(2)

This is true for all A such that 0° ≤ A ≤ 90°

So, this is a trigonometric identity.

Let us now divide (1) by AB2, we get:

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}^{2}}{\mathrm{AB}^{2}}+\frac{\mathrm{BC}^{2}}{\mathrm{AB}^{2}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}^{2}}{\mathrm{AB}^{2}}\)

or

\(\left(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AB}}\right)^{2}+\left(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{AB}}\right)^{2}=\left(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AB}}\right)^{2}\)

i.e., 1 + tan2A = sec2 A …(3)

Let us see what we get on dividing (1) by BC2. we get:

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}^{2}}{\mathrm{BC}^{2}}+\frac{\mathrm{BC}^{2}}{\mathrm{BC}^{2}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}^{2}}{\mathrm{BC}^{2}}\)

i.e \(\left(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BC}}\right)^{2}+\left(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{BC}}\right)^{2}=\left(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{BC}}\right)^{2}\)

i.e., cot2A + 1 = cosec2 A …(4)

Using these identities, we can express each trigonometric ratio in terms of other trigonometric ratios.

i.e., if any one of the ratios is known, we can also determine the values of other trigonometric ratios.